This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Health Science magazine, the member magazine of the National Health Association.

If we are unskilled at the squat, we may have trouble getting in and out of our bed or car, tying our shoes, or picking up things we’ve dropped. In addition, climbing stairs, playing sports, and standing up after a fall can feel prohibitively challenging and painful. Each of these limitations can ultimately lead to diminished independence.

Athletes must also be able to execute an excellent squat, enabling basketball players to shoot free throws and downhill skiers to navigate moguls. Though its application may differ, the squat’s necessity is ubiquitous.

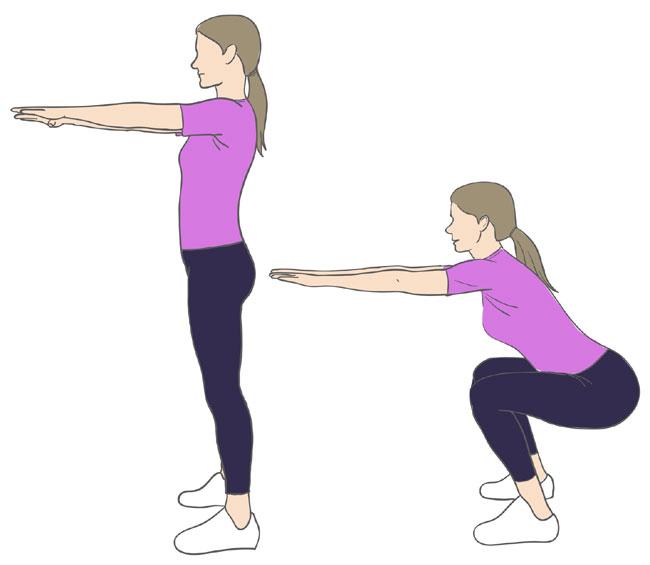

So how do you do a squat? Let’s break it down:

- Begin with feet shoulder-width apart and parallel to each other. If your hips are tight, you may need to move your feet just outside shoulder width and/or turn your toes out.

- Shift your weight over the arches of your feet and engage your midsection, as though you were bracing to take a light punch. Squeeze your glutes to “lock out” your hips. This is both the starting and finishing position.

- Keeping your weight in the mid-foot, descend by reaching your hips back and allowing your knees to move forward. Your heels and toes should be in contact with the ground, and your torso will likely lean forward a bit, which is fine.

- At a certain depth (it’s different for everyone), your lower back will begin to round. Stop just before this point. Stand back up by squeezing the glutes and driving the hips forward as your knees extend. This will bring you back to step 1.

Performing certain basic movements are as essential to our musculoskeletal health and quality of life as eating certain basic foods are to the vitality of our entire body. Squats are one of the tried and true exercises that all bodies were built to perform—they are the very definition of functional.

Whether I’m training an offensive lineman or my grandmother to squat, I must first consider their respective needs. An offensive lineman needs to plow through the brick wall of defensive linemen before him. My grandmother, on the other hand, would love to be able to stand up easily. Both must learn to perform the same squat, though the squat must be made more difficult or “progressed” for the lineman, and easier or “regressed” for my grandmother. Both must become adept squatters to accomplish their respective goals.

Progressing the offensive lineman’s squat is actually fairly simple. Its challenges are more mathematical, involving altering the weight used, the number of sets and repetitions performed, and/or modifying the speed of the movement. The squat stays the same, but the parameters change. Regressing my grandmother’s squat, however, might be met with more controversy.

Different Approaches

Many trainers and coaches would prescribe different movements to strengthen each respective muscle involved in the squat. They might have my grandmother work through the equipment at her fitness center, using the knee extension machine for her quadriceps, the leg curl machine for her hamstrings, and the hip extension machine for her glutes. Their rationale would be that by individually strengthening each major muscle of her upper leg, her squat will improve because the pieces are stronger. Let’s call this the “Parts” approach since it aims to improve each disparate part of the system.

Another strategy is the “Whole” approach, which I like. It requires the whole body to move as one to accomplish small portions of the end-goal movement. I would teach my grandmother to squat, with impeccable form, to a shallow depth, perhaps just an inch or two down from standing. I might standardize her range of motion by instructing her to lower her bottom onto a stool or other surface of appropriate height so that her buttocks touch the surface on every repetition. As she practices and becomes increasingly adept, I would deepen her squat while ensuring that her movement retains integrity. To achieve more depth, I might stack several phone books on a chair, removing them one at a time as she gets stronger.

What distinguishes the “Parts” and “Whole” strategies? Most obviously, the Parts approach uses machines while the Whole approach demands nothing more than a body in space. Second, most weight machines permit movement in just one plane, but the squat requires simultaneous movement in more than one plane: grandma’s muscles must continually work to maintain her body position, improving her balance and stability in the process. This is clearly an added bonus for an older woman whose demographic already places her at heightened risk of falls and hip fractures.

Another distinction between the two approaches is that all of the Parts exercises are considered “open chain.” This means that only the limbs move while the rest of the body stays still. To illustrate this, remain seated and simply extend one of your legs. Did your belly button move? No. Now stand up from your chair. Did your belly button move? Yes. As a general rule, if your belly button doesn’t move during an exercise, the movement is considered “open chain.” If your belly button moves, the movement is called “closed chain.”

Many movements in life are open chain, like brushing your teeth and waving hello. These require minimal use of core musculature and most people have no problem performing them. Closed chain movements like the squat, on the other hand, are more involved and usually more difficult. They use more musculature and translate more effectively to challenging movements like lifting a box off the floor and walking up a flight of stairs.

The differences between the Parts and Whole strategies continue. Parts movements are “isolated,” requiring the use of only one joint. Whole movements are “compound,” requiring more than one joint. In general, the more muscles we engage per movement, the more bang for our buck. Whole movements set off a superior hormonal response, causing more calories to be burned and more muscle to be built.

The two approaches also impose different demands of time and space. The machine-training route requires my grandmother to perform three exercises to train her lower body. The squat, a single exercise, trains these same muscles and others, too. Furthermore, the machine program adds the barrier of my grandmother needing to go to the gym. In contrast, she can easily perform body weight squats at home or while travelling.

For a movement to earn its place at the foundation of a training program, it should satisfy all three criteria: close chain (belly button moves), compound (uses more than one joint), and machine-free (or free-standing).

Application

Let’s look at some specific benefits and recommendations for executing squats by children/adolescents, adults, and older adults.

Children and adolescents:

Benefits:

- Preserve range of motion (ROM). ROM is much easier to maintain than to build back once lost.

- Increase bone density and prevents osteoporosis. Take advantage of the fact that we build the most bone before age 30.

Recommendations:

- Perform 1–2 sets of 6–15 repetitions. Rest 1–3 minutes between sets.

- Resistance can be increased by 5–10% by holding free weights or simply wearing a backpack once 15 repetitions can be easily performed.

- Complete on 2–3 nonconsecutive days of the week.

Healthy adults:

Benefits:

- Prevent and improve depression and anxiety, increase energy levels, and decrease fatigue.

- Improve body composition.

Recommendations:

- Perform 2–4 sets (as few as 1 for novices) of 8–12 repetitions. Rest 2–3 minutes between sets.

- Resistance can be increased by 5–10% once 12 repetitions can be easily performed.

- Complete on 2–3 nonconsecutive days of the week.

Older adults (65+ years old):

Benefits:

- Improve balance to reduce risk of falling.

- Prevent, slow, or even reverse the loss of bone in those with osteoporosis.

Recommendations:

- If necessary, hold a rail or supportive structure for balance when learning to squat. Aim to reduce the use of support until none is needed.

- Perform 1–3 sets of 10–15 repetitions. Rest 2–3 minutes between sets.

- Resistance can be increased by 5–10% once 15 repetitions can be easily performed.

- Complete 2–3 nonconsecutive days of the week.

Squats offer a highly effective means to increase fitness and facilitate activities of daily living with ease and without pain. The squat and its variations can be found in movements as general as sitting into and standing up from a chair, and as specific as a jump shot in basketball.

Squats require no equipment, strengthen the muscles of the core and lower body, and when done correctly, build bones, preserve joint range of motion, and improve our state of mind. Squats are undoubtedly an all-star exercise that should be incorporated into each of our lives.

Resources (for applications):

Children and adolescents